The Fourth Amendment: Protecting Privacy and Possessions

Imagine if any police officer or government agent could search you or your home and take anything they wanted.

By: James Fite | October 7, 2021 | 706 Words

(Photo by Mario Villafuerte/Getty Images)

Imagine government agents and police searching your home – without your permission or any evidence that you’ve broken the law – and taking whatever they want. As crazy as it may sound to a modern American, it was normal for British tax collectors to do just this back before the Revolution.

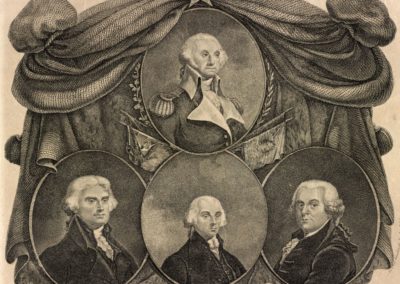

The Founding Fathers carefully created the Constitution and Bill of Rights to protect the people from government abuse. It was that very behavior by the British that inspired the Fourth Amendment. It states:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

What does it mean to be secure? It means that Americans have the right to privacy, as well as the right to possess things. So, if you have something in your pocket, in a purse, or in a backpack, for example, the police generally can’t just demand you reveal it to them. The same goes for your home. If you’re carrying a letter or a book, the police don’t have the authority to demand you let them read it.

The Fourth Amendment doesn’t just tell the government to mind its own business; it also tells the government to keep its hands off your stuff. Say you have a big-screen TV and a gaming console at home, and you always have your smartphone on you when you go out. Thanks to the Fourth Amendment, it’s illegal for government agents of any kind to snatch your phone out of your hand or kick in your door and take your TV.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the police can never search you or your home, or take anything from you. If law enforcement can show “probable cause” to believe you’ve committed a crime, a judge might sign a warrant, allowing officers to conduct a search and seize any evidence. Also, there’s a bit of wiggle room in restricting only “unreasonable” searches and seizures. Who gets to decide what’s reasonable and what isn’t? There are some guidelines, but ultimately, it’s up to the courts to decide if a police action is lawful – and that happens after the event.

Since people can challenge searches and seizures in court, a lot of things have changed over the years since the founding. If a judge finds that an officer did violate a person’s Fourth Amendment rights, then the rules may change for how the police act. On the other hand, if the judge rules that the search or seizure was reasonable, that scenario is likely to be seen as an exception to the Fourth Amendment from then on. Many times, this happens because of new technology that didn’t exist when the Bill of Rights was written. For example, do you have the right to resist warrantless searches in a car? How about the right to keep your emails, texts, or the photos on your phone private?

Today, the Fourth Amendment is a confusing topic. Courts have ruled that, in most cases, Americans are as secure in their cars as they are in their homes. They also found that the contents of phones, computers, email accounts, and text messages are no different from the “papers and effects” covered in the amendment.

Today, the Fourth Amendment is a confusing topic. Courts have ruled that, in most cases, Americans are as secure in their cars as they are in their homes. They also found that the contents of phones, computers, email accounts, and text messages are no different from the “papers and effects” covered in the amendment.

But there are exceptions. Airport security searches people every day – and anyone who wants to fly must first surrender some privacy. When pulled over in a car, anything the officer can see inside the vehicle can be seized or trigger a more thorough search without a warrant. Those are just some of the most common exceptions. Then, of course, there is no Fourth Amendment protection for when the police act in response to an emergency.

But don’t let the exceptions to the rule take away from the importance of the Fourth Amendment. Remember those British tax collectors the Founders had to deal with? Life in America could be a whole lot worse!