How Has the Bill of Rights Changed?

The Bill of Rights we have today wasn’t the version first put forth.

By: Kelli Ballard | December 15, 2022 | 853 Words

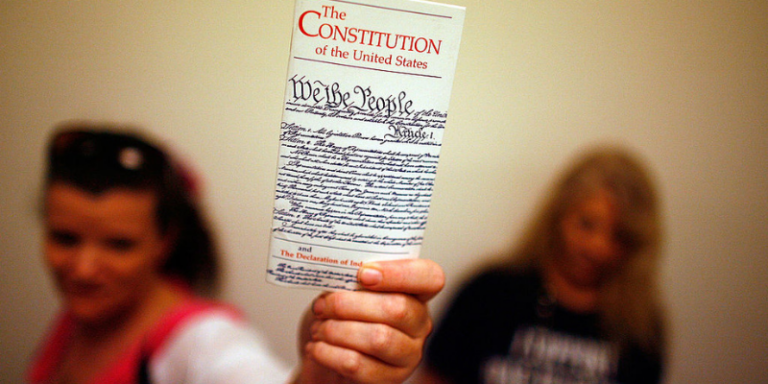

(Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are the founding documents of the United States. A good deal of work – and debate – went into each, and so the Bill of Rights we know today is a bit different from the original idea.

The U.S. Bill of Rights wasn’t the first in the country. Each state already had its own constitution, and many protected the rights of the people. George Mason was the lead writer for Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, which served as a model for many to come, most famously the U.S. Bill of Rights. While discussing the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 in Philadelphia, Mason said that he “wished the plan had been prefaced by a Bill of Rights” for the nation.

There was a lot of argument over the issue, but it wasn’t about whether or not the people had natural rights. Those who didn’t want the rights of the people to be explicitly stated saw two problems: First, they thought that the Constitution itself was enough. Second, they worried that the wording of a bill of rights could be used by future leaders to actually violate the rights of the people, either by twisting the meaning of the amendments or by ignoring any right that wasn’t written in the document.

James Madison

(Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images)

In fact, the Bill of Rights nearly wasn’t written at all. Even James Madison, who wrote the Bill of Rights, didn’t think America should have one. Mason and others argued that it was needed, and in the end Madison promised to support the idea.

Even then, the First and Second Amendments were almost something entirely different. Madison proposed 19 amendments and the House sent 17 of them to the Senate, which were then consolidated into the 12 amendments that went to the states.

The first two were not ratified immediately. Had they been, our First Amendment today would have established “a detailed formula for the number of House members, based on each decennial census,” said Andrew Glass at Politico. If the amendment has been adopted “today’s House would have either 800 or 5000 representatives,” he added. Currently, there are 435 members. The second amendment at the time regulated payment for members of Congress. It was not ratified for another 203 years and became the 27th Amendment.

What else was left out of our final version of the Bill of Rights? Madison originally wanted the Constitution to have a two-part Preamble that would include part of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. Madison told the congregation:

“First. That there be prefixed to the Constitution a declaration, that all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.

That Government is instituted and ought to be exercised for the benefit of the people; which consists in the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right of acquiring and using property, and generally of pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

That the people have an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform or change their Government, whenever it be found adverse or inadequate to the purposes of its institution.”

If Madison had his way, “We the People” would have been buried in the middle, and it’s likely it wouldn’t have ended up as powerful a message. Roger Sherman of Connecticut questioned the placement of the phrase, arguing:

“The truth is better asserted than it can be by any words what so ever. The words ‘We the People’ in the original Constitution are as copious and expressive as possible.”

Congress eventually deleted Madison’s pre-Preamble as the Bill of Rights made its way through the approval process. The future president continued with his suggestions, saying all states should have at least three liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights: “No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.”

One of Madison’s biggest concerns was making sure the government didn’t overreach its powers. He told Congress:

One of Madison’s biggest concerns was making sure the government didn’t overreach its powers. He told Congress:

“The powers delegated by the Constitution are appropriated to the departments to which they are respectively distributed: so that the Legislative Department shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial, nor the Executive exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial, nor the Judicial exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive Departments.”

Madison also had a different wording in mind for the Second Amendment – which would have been the Fourth Amendment in the original draft: “A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.”

The Bill of Rights went through many changes and faced great opposition. In the end, the Framers were able to come to an agreement despite the many opposing viewpoints.