Baseball and Economics: Part II

There’s more economics to baseball than you might have known.

By: Andrew Moran | January 24, 2020 | 537 Words

(Photo by Al Bello/Getty Images)

There is a lot that baseball can teach us about economics. In part one, we looked at creative destruction, subjective value, and how both economic principles are at play in baseball. Now let’s examine a few more.

Self-Regulating Markets

You may have heard about the Houston Astros’ sign-stealing controversy from the 2017 season and postseason. If you have not, let’s just say that it consisted of overhead cameras, trashcan banging, and whistling. While many teams and players suspected foul play on the part of the 2017 World Series champions, nothing was ever proven.

Sign-stealing is common in baseball, just not on the alleged level of the Astros. A runner on second base, for example, can try to determine what the pitcher is going to throw and then convey to the hitter what type of pitch he can expect. Teams are, rightfully, so paranoid about sign-stealing that they have taken matters into their own hands.

If you watch a random MLB broadcast, you might notice the back catcher delivering multiple signs to the pitcher. The purpose of this act is to ensure that the opposing squad cannot quickly and accurately determine the signal.

Rather than wait for rule changes or bans, some teams are attempting to eliminate sign-stealing with complex signs and unique communication. Should clubs fail to correctly decipher what signs are being shown, they will inevitably shut down operations and try to win games by just being the better team through tactics and athleticism. This is how markets regulate themselves without any state interventions.

Labor Negotiations

In baseball, there is no salary cap, meaning teams can spend any amount they wish on a player of their choosing. Depending on the state of the market and the teams’ needs, elite athletes usually have the advantage. They typically demand a few things: dollar-amount, length of the contract, and average annual value (AAV). A team may offer a five-year deal worth $143 million, but a player may request a six-year deal valued at $146 million.

To get what they want, athletes will have the best people around them negotiating and ironing out the terms and conditions of a lucrative contract. General managers may attempt to sweeten the pot by throwing in incentives: If a player finishes in the top ten of MVP voting each season, then he will earn an extra $2 million a year – or a pitcher may need three consecutive seasons of 200 or more innings to receive a $4 million bonus and a club option.

To get what they want, athletes will have the best people around them negotiating and ironing out the terms and conditions of a lucrative contract. General managers may attempt to sweeten the pot by throwing in incentives: If a player finishes in the top ten of MVP voting each season, then he will earn an extra $2 million a year – or a pitcher may need three consecutive seasons of 200 or more innings to receive a $4 million bonus and a club option.

Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. The point is all about labor relations and how employers and employees agree on a working partnership.

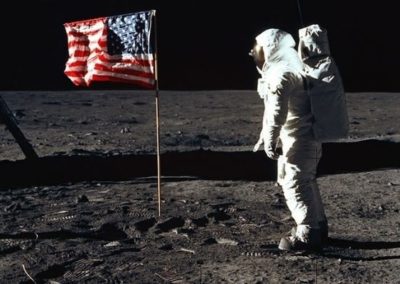

As American As Apple Pie

Today, every team’s front office is filled with employees holding degrees in economics, mathematics, or data science. Baseball was always a game of strategy, but now this has morphed into intricate and obscure measurements, such as xFIP, BABIP, and REW – all Sabermetrics that would trigger headaches for non-baseball fans and non-STEM majors. Key performance indicators are critical to the sport, but baseball is also a fantastic physical display of the various laws and principles of economics. In a world where this discipline is portrayed with great disdain, baseball can breathe some life into the science.