The Political Origins of Columbus Day

Worried about losing an election, President Harrison tried to attract Italian American votes.

By: Kelli Ballard | October 13, 2025 | 590 Words

Christopher Columbus, detail of painting by Peter Johann Nepomuk Geiger. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Columbus Day celebrates an Italian explorer. Spain sent him to find a better trading route, but he was credited with discovering America by mistake. For centuries, Christopher Columbus and his “discovery” have been celebrated in the United States. But how did this holiday first get started? The first time a national event celebrated Columbus, it was not designed to honor the man. Instead, it was a political move during a re-election campaign.

The First Columbus Day

The first known Columbus Day festivities were held in 1792 by the New York Columbian Order. The day was celebrated by the Italian and Catholic communities. It didn’t become an official holiday until 1892, when President Benjamin Harrison made a proclamation to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage. He wrote:

“On that day let the people, so far as possible, cease from toil and devote themselves to such exercises as may best express honor to the discoverer and their appreciation of the great achievements of the four completed centuries of American Life.”

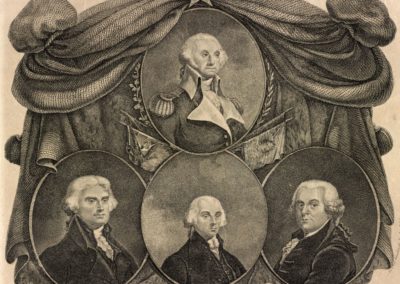

However, honoring Columbus was not the true goal. Instead, Harrison was trying to solve a diplomatic crisis with Italy and hoping to gain support from Italian American voters.

A Crisis With Italy

The crisis began when a group of Italian immigrants was killed in New Orleans. In March 1891, six Italians were acquitted of murdering a police chief in the city. It was rumored that the jurors had been bribed by powerful Italian families who were involved in crime. The next morning, thousands of people arrived at the Orleans Parish Prison, where six of the defendants and 13 other Italian suspects were captive. A group of armed men broke into the jail and killed nine of the prisoners. Italian immigrants at the time were highly discriminated against, and newspapers painted the prisoners’ murders in a good light. Even Theodore Roosevelt, a U.S. Civil Service commissioner at the time, didn’t condemn the event. He wrote to his sister that, “Personally, I think it a rather good thing.” This reaction angered Italians, both in America and their homeland. Italy ended diplomatic relations and called its ambassador away from the U.S. There was even talk of war brewing. It wasn’t until months later that President Harrison finally spoke against the murders, describing them as “a most deplorable and discreditable incident” and an “offense against law and humanity.”

Benjamin Harrison (Photo by Interim Archives/Getty Images)

Winning Back Italians

Italy demanded that America pay money to the relatives of three victims, who were Italian citizens. Harrison agreed. But it was an election year. Somehow, Harrison had to gain the support of Italian voters in America. The Brooklyn Citizen wrote:

“… the approaching Presidential election and the necessity the President feels under of repairing his political fences in every direction … He does not want to have the Italian vote massed against him.”

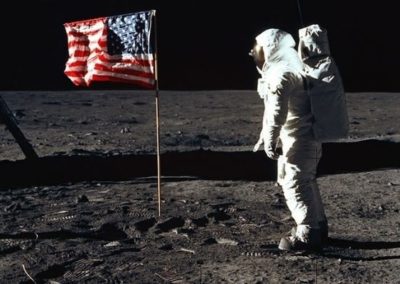

Harrison met with Francis Bellamy, who encouraged a national holiday to promote patriotism among schoolchildren. Bellamy had written “The Pledge of Allegiance” for that meeting. Liking the idea, Harrison took it to Congress. A one-time holiday was held to celebrate Columbus to “impress upon our youth the patriotic duties of American citizenship.” Even so, Columbus Day did not become a yearly national holiday until 1934, after the Knights of Columbus lobbied Congress. President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the holiday. The second Monday in October was declared the specific holiday in 1971.