Rutherford B. Hayes: The First President to Lose the Popular Vote

Hayes went to bed thinking he had lost – but he had won the electoral vote.

By: Kelli Ballard | February 28, 2020 | 380 Words

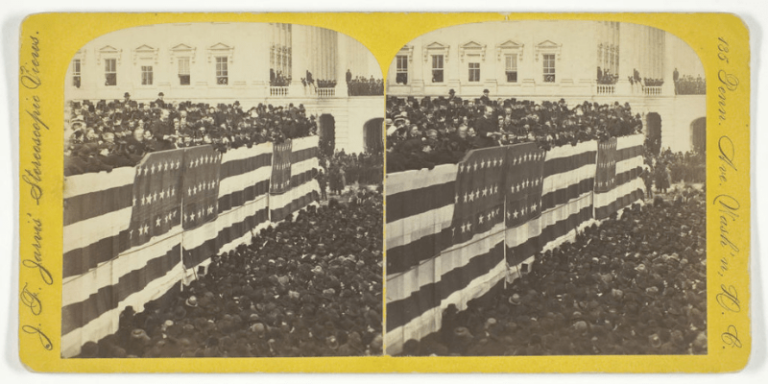

Inauguration ceremony of President Rutherford Birchard Hayes (Photo by by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Rutherford B. Hayes (1822–1893) became the 19th president of the United States in 1877. He was the first president to be elected by the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote, which earned him the nickname “His Fraudulency” by his opponents.

Hayes was born on Oct. 4, 1822 in Delaware, Ohio. His father had passed away just two months before his birth. He received his education at Kenyon College and Harvard Law School and then practiced law for about five years.

Tilden-Hayes Affair

(Getty Images)

Hayes ran for president in the 1876 election, but it looked like the Democrats were going to win, so he went to bed that night thinking he had lost. The Republican National Chairman Zachariah Chandler found a loophole and sent a wire saying “Hayes has 185 votes and is elected.” Samuel J. Tilden had the popular vote with 4,300,000, while Hayes had 4,036,000.

The presidential seat now depended upon electoral votes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, which had been contested by Hayes’ campaign managers. For months, Congress tried to figure out how to accurately tell the results and finally created an Electoral Commission to make the decision. On March 2, 1877, the Commission decided that all the contested votes would go to Hayes, making the final tally 185 for Hayes and 184 electoral votes for Tilden. This contentious dispute became known as the Tilden-Hayes affair.

President Rutherford B. Hayes

The Civil War had caused a lot of bad feelings between the Southern and Northern states. Hayes wanted to try and heal some of the rifts and included an ex-Confederate to his staff, which outraged some of the Northern supporters. He appointed more Southerners to federal positions and kept his promise to withdraw the troops from states that were still under occupation, which led to the end of the Reconstruction era.

Hayes’ presidency had been about building up the South and strengthening the Republican Party; however, the hostility between the northern and southern states was still too great and ended up almost virtually destroying the Republican Party in the South.

He chose not to run for president for another term and in retirement devoted his time to other causes such as educational opportunities for black youth in the South and prison reform. He died on Jan. 17, 1893 at the age of 70.