Christmas and the Civil War: Bringing Hope and Cheer to Hard Times

Before the war between the states, Christmas was not the merry holiday we know today.

By: Kelli Ballard | December 22, 2021 | 655 Words

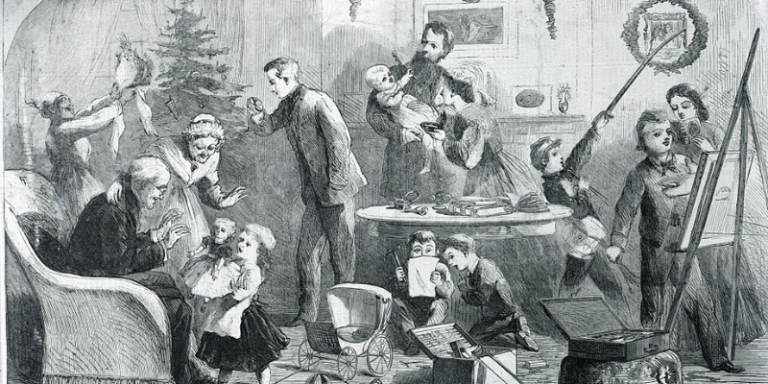

Christmas presents shortly after the Civil War. Sketched and drawn by S. Eytinge. (Getty Images)

Christmas wasn’t always the merry holiday we know today. Many Christians refused to celebrate or honor it, as the date was associated with the Pagan winter solstice. For others, Christmas was a time for solemn prayer. So, what happened to change a somber December 25 into today’s holiday? Oddly enough, the Civil War had a hand in giving us a more cheerful season.

Christmas was not an official holiday in the U.S. before the Civil War, and in some places, people were even punished for trying to celebrate. For example, in Massachusetts during the 17th century, colonists received a fine if they dared to honor the occasion.

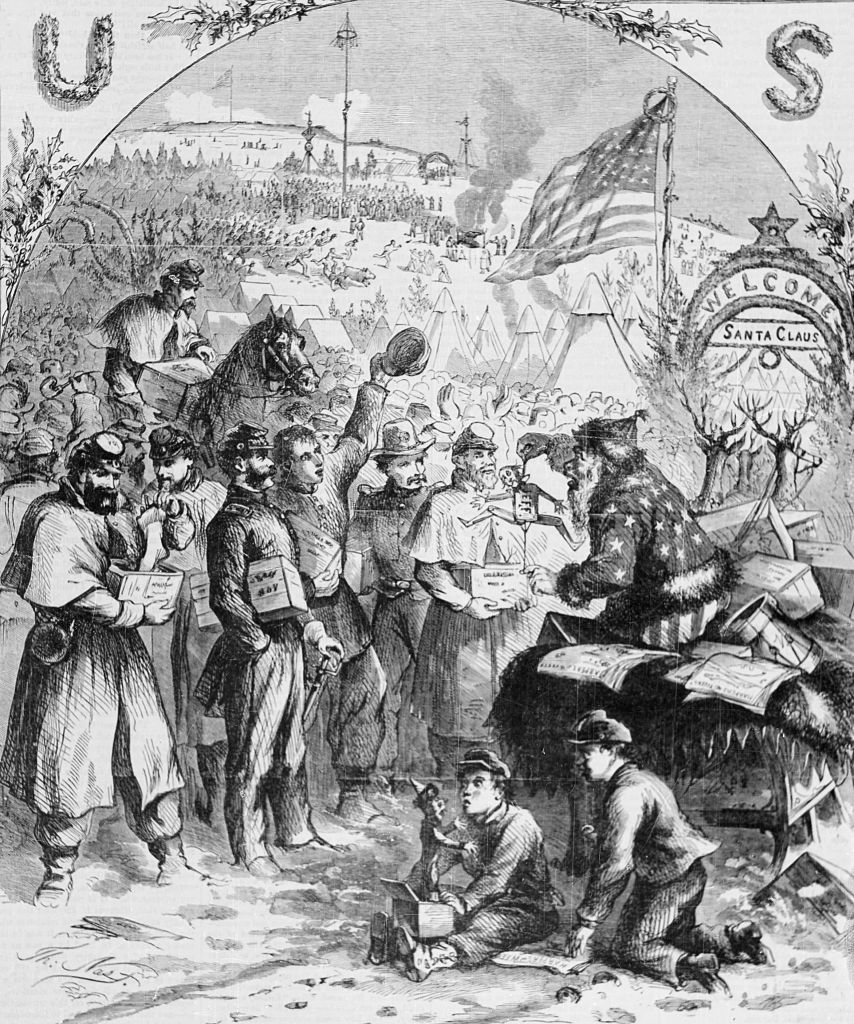

Christmas Eve, 1862. Artist Thomas Nast. (Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

The Victorian era (1837-1901) in Britain helped to make certain holiday traditions more popular, such as Christmas trees and decorations, singing carols, gift-giving, and holiday cards. Many of these traditions traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to become common in America. The U.S. Civil War occurred during the same time period – from 1861 to 1865. Modern Christmas traditions became popular during and after the Civil War.

As the country was split with the North fighting the South, times were difficult and Christmas was fraught with worry, depression, and poverty. Although some of the most popular songs and poems, such as “Jingle Bells” (1857) and “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (1823), had started growing in popularity, people were not in the jolly mood. Many women, on both sides of the war, spent the time making clothes for soldiers and working in the hospitals. Some prepared holiday food boxes and fruit. Gifts were changed from store-bought items to whatever could be handmade, such as popcorn balls or homemade toys.

Christmas during the Civil War: Santa Claus in camp, 1863.

In 1862, illustrator Thomas Nast drew an image of Santa Claus dressed in the star-spangled banner. Published in Harper’s Weekly, the image showed St. Nick handing out good cheer to Union soldiers from his sleigh. But for children in the Southern states, parents warned that Santa Claus might not visit that year. According to historian James Alan Marten, a Confederate family’s children were told “not to expect a visit from St. Nick because the Yankees had shot him.” Luckily, Santa survived the Civil War! Other Southern families said he couldn’t visit because he “would be held up by Confederate pickets or perhaps Union blockading vessels had interrupted his journey.”

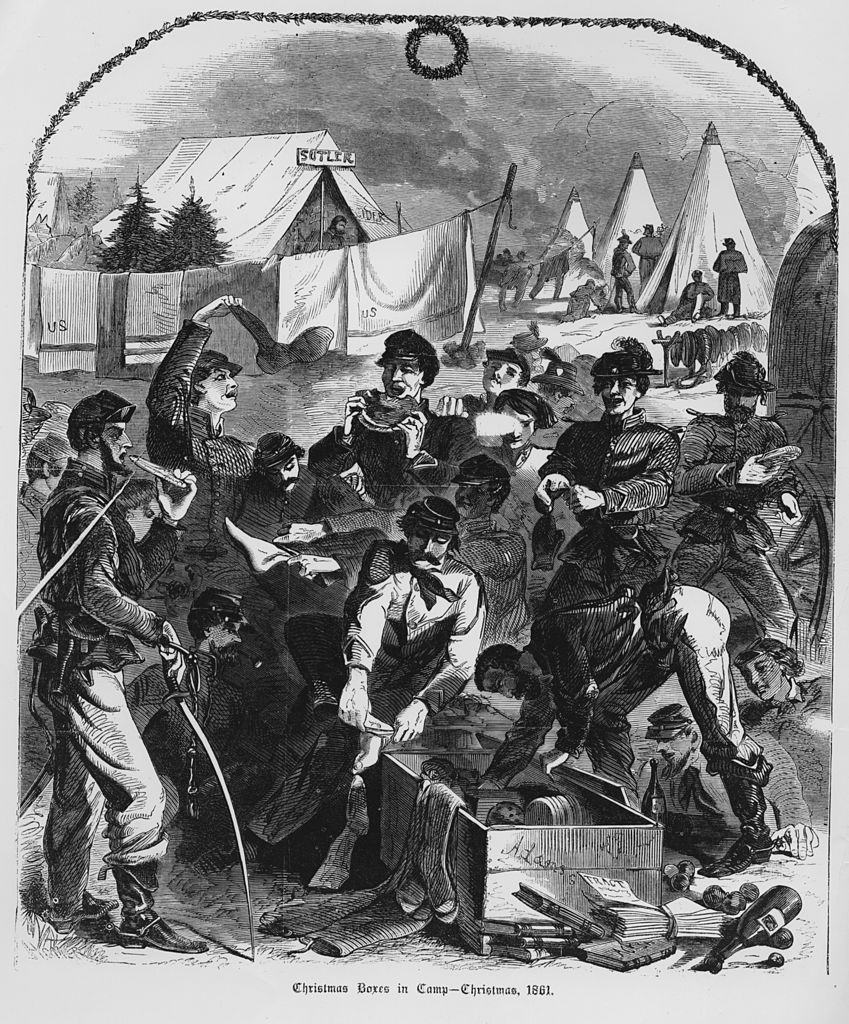

For soldiers, the holiday was both melancholy and hopeful. It could be a break in the battles and woes of war. Alfred Bellard, a soldier of the 5th New Jersey regiment, wrote, “In order to make it look much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked off with hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc.” John Haley of the 17th Maine wrote on Christmas Eve in his diary that:

“It is rumored that there are sundry boxes and mysterious parcels over at Stoneman’s Station directed to us. We retire to sleep with feelings akin to those of children expecting Santa Claus.”

Union soldiers opening Christmas boxes in camp during the US civil war, December 1861. (Photo by American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Despite the hard times and the country being ravaged by war, families still found a way to modestly celebrate. As historian David Anderson said, “The Christmas season [reminded] mid-19th century Americans of the importance of home” and tradition.

Magazines and newspapers played a big role in promoting Christmas as a time for joy and sharing. After the war, they continued to talk about the importance of the season. In 1870, a few years after the war ended, Congress passed a law to make Christmas an official holiday in the United States.